Themes in this post: Developers | Installers

Perhaps the first prominent solar power plant developer I actually met face to face was Inderpreet Wadhwa, founder of Azure Power.

A suave chap sat next to me at a conference in Delhi in 2010, and we got up chatting. He told me he was the founder of a solar power plant development firm and was planning to install many MWs of capacity in India. He told me his name was Indrepreet and his company was Azure Power. Neither rang a bell for me at that time, but I soon realized that his firm was one of the first solar power developers in India with big plans.

I assumed Inderpreet had an engineering work experience, and was thus surprised that he actually had an MBA in Finance from University of California and had mostly been working in software and management positions. This happened to be the first of many times I met founders and owners of solar power plants who had nothing to do with power or infrastructure.

Inderpreet and many other enterprising folks ventured into India’s solar power sector as developers and/or installers.

Unless you are talking about small solar power plants – say, less than 100 Watts, those that are used for solar lanterns etc., or small residential rooftops of 1 KW or less – installing solar power plants can require significant upfront costs. These costs have come down dramatically in the last decade, but they still cost a packet.

Hence, for any sizable solar power project, there are two types of stakeholders who are intimately connected with it – #Hsomeone who owns the project#H, and #Hsomeone who constructs it#H.

The owners are the ones who invest their money and are typically called Developers.

The installers or construction companies are called EPC companies – the acronym standing for Engineering Procurement and Construction.

In some cases, the developer and installer can be the same, but in many cases, these are two different companies.

Let’s learn more about these two stakeholders.

Developers

So, these are the folks that, as owners of the project, put real money on the table to develop the solar power plants.

A developer has multiple tasks to perform before he can generate the first unit of electricity from the power plant.

Assuming the developer has control over the land for the solar power plant, more than anything else, he first needs to figure out who would be buying the power generated from the solar power plant. This is critical. Many have been the times when we had enthusiastic businesses call us to enquire about putting up solar power plants. They have large amounts of land, they have investible surplus funds, and they are raring to go. Until the time when I ask them, “Who will purchase the solar power?.” And then there is quiet on the other side.

Different entities can purchase solar power. Mostly, these are central government or state government power companies or corporate businesses. Once they decide to buy power from your solar power plant, they usually sign a long term PPA (power purchase agreement), for anywhere between 15-25 years. Developers can get to know about these power purchase opportunities through government or private tenders. For getting private PPAs, the most common method to get it is the good old way of disciplined business development.

Once a developer has a valid PPA in hand, the rest of the steps follow – getting approval from banks for financing, scouting for a good EPC to put up the power plant, getting the necessary approvals for laying the connection from the solar power plant to the nearest sub-station.

Once all these are completed, the construction of the solar power plant begins.

For a decent sized solar farm, say about 100 MW, the whole process, from identifying land to generating the first unit of power could take 6 months. Once done, the plant operates fairly smoothly for the next 25 years.

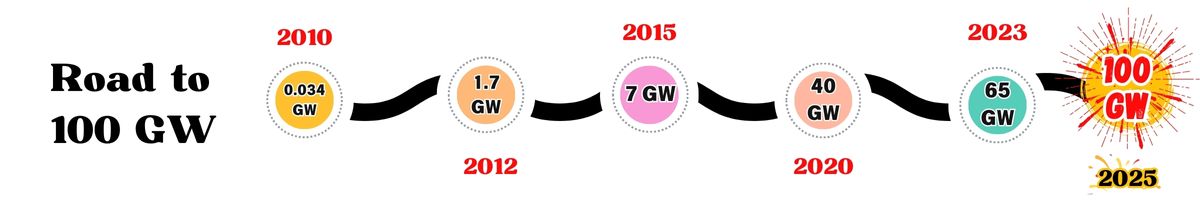

Starting 2010, India has seen a number of companies developing small, medium and large-scale solar power plants.

Prominent solar power sector developers include Tata Power Solar, ReNew Power, Adani Green, Sembcorp and Greenko. There are hundreds of smaller developers too, many of who will be owning just 1 or 2 MW of solar power assets.

As of early 2025, the characteristics and extent of involvement of these companies in the solar PV ecosystem are still evolving. Companies such as Tata Power Solar, which has had a long history in this sector, are currently operating along most of the value chain – from cell and module making to themselves being EPCs and finally developing solar power plants. Companies such as Azure and ReNew Power had been focussing mostly on being power plant developers thus far, but some of them are also making vertical integration forays through efforts in manufacturing of solar cells and panels.

Companies such as ReNew Power and Greenko are homegrown developers and IPPs (independent power producers) while developers such as Sembcorp, a company that has been investing heavily into Indian renewable energy power plants, represent international investors and developers.

Adani Green is another prominent developer. Though a relative latecomer to the Indian solar power scene, the group has big ambitions and has in a short time invested in developing over 7.5 GW of solar as of end 2024. But in addition to being a developer, the company has invested along the entire solar PV value chain, and could soon be one of the largest producers of solar cells and modules in India.

Installers

Solar power plant installers, also called EPCs (Engineering, Procurement, and Construction) are the companies that transform sprawling fields and empty rooftops into power generation systems.

So what does each of the three stages – Engineering, Procurement & Construction – comprise?

Engineering: Mostly comprises planning and design, and includes initial feasibility studies to the detailed design of the solar power plant. Whether it is a small rooftop or a large solar farm, this design/engineering stage is critical to ensure that the power plant will function well for 25 years. This stage is super critical for large solar farms where, besides the large project lifetime, very large sums of money are invested into a plant. In India, a total project investment of about $400 million could be required for a 1 GW (1000 MW) solar power plant, and these plants typically will be working at remote regions across summer and winter, in hot sunshine and rains and dust storms for 25 long years. Imagine if this plant has fundamental design issues. The country has already had horror stories of solar panels flying off from the ground during strong winds – most of these incidents would not have happened if the engineering & design had been done much better.

Procurement: This is a fairly well-known component – involves procurement of solar panels, inverters, mounting structures, cables, and other essential components. In most cases, procurement is directly handled by the EPC firms with oversight from the project owner (developer) only on key aspects – owner’s typically have a project manager or an “owner’s engineer” supervise such EPC procurement. Prominent EPC companies leverage their relationships with suppliers to procure high-quality materials at competitive prices, and smart EPC companies make some increases to their profit margins if they can get a good bargain. Where the EPC work is done by the developer company (as is the case for many large companies), getting great deals for high quality components decreases the overall project costs while increasing the project performance and returns.

Construction: This is the most visible phase of an EPC’s work – the actual construction of the solar power plant. This itself can be divided into preparation stage (involves mostly site preparation and also ensuring all permits and approvals have been obtained), installation stage (installing solar panels, and other balance of systems), and commissioning stage (includes testing, connecting to the grid and final approvals). The actual construction phase alone could take about 6-8 months for a 1 GW (1000 MW sized solar farm), and in select cases, up to a year. These are relatively short durations – building equivalent capacities of coal, hydro or nuclear power plants could take a lot longer!

O&M – O&M, which stands for Operations & Maintenance, is not a core part of an EPC’s scope of work because this is needed in an ongoing basis for a solar power plant over its 25 year lifetime, but in many cases, EPCs also sign up for O&M as it makes easy for the developer to run the plant and it also provides a steady, continuous stream of revenues for the developer. A solar power plant does not require much maintenance as there are no moving parts – this indeed is a key strength of solar PV! But it does require some maintenance in terms of cleaning the panels of dust, bird droppings etc., and also regular monitoring to ensure the power plant is yielding the electricity it is slated to, and where are gaps, identify issues and take corrective action. There might be selective cases where some panels may have to be replaced for glass breakage, or damages from short circuits or heat. Regular checking and maintenance of electrical cables etc., need to be done too.

As you can see, there’s a lot of work an EPC has to do to earn his bread!

Some data indicate that India might have close to #H5000 EPCs small and large#H. That’s a pretty large number of businesses formed in a fairly short time, but this should not be surprising.

Not surprising because you see, starting an EPC business does not need any capital investment. If you are good at electrical and civil works and can get some guys good at solar power plant design and installation, you are all set to go. Of course, you might need much more than these credentials to qualify for large solar farm installations, but for rooftop solar and small scale ground mounted solar power plants, becoming an EPC is fairly easy.

Many EPC companies comprise just a couple of people, most times just the promoters. They do the main business development, design and procurement work, and sub-contract most of the civil and standard electrical works to others. This way, they are able to stay lean and profitable.

EPC companies make reasonable profits, something in the 5-7% range on the total installation cost of a solar power plant. Given that it costs about #HRs 3 crores per MW#H of a solar power plant, a 10 MW power plant can put about Rs 2 crores into an EPC company’s hands – not a bad sum for a 3-month project with no upfront costs, what do you say?

While a large proportion of the EPCs out of the 5000 odd list will be literally unknown outside of their towns or cities, there are some large and prominent ones. These include L&T, Sterling & Wilson (part of Shapoorji Pallonji group), Tata Power Solar, Vikram Solar, Mahendra Susten etc.

If you had heard most of these names even before the solar power sector started blossoming, it should not be surprising because many of them, especially L&T and Sterling & Wilson have been in the installation & EPC business for other sectors such as infrastructure & buildings for a long time, and these companies are now leveraging their decades-long expertise and experience for the solar power sector.

Many EPCs – especially the larger ones such as L&T, Tata Power, Sterling & Wilson – have a much higher focus on the ground-mounted solar power plants. EPCs such as L&T and Sterling & Wilson have been instrumental in the construction of some of the largest solar parks in India.

Some installers such as CleanMax Solar, Amplus Solar, Fourth Partner Energy, and Cleantech Solar are more focussed on the commercial and industrial rooftop segment.

For the rooftop solar power plant of Maruti Suzuki’s manufacturing plants at Gurugram & Manesar (Haryana), CleanMax Solar was both the developer and EPC, as this was built on the OPEX model where CleanMax built and owned the plant, and Maruti paid them based on consuming the power generated, at a negotiated tariff. For the Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages’ Bottling Plants’ rooftop solar systems, Amplus Solar was the developer and EPC. For Wipro’s Sarjapur (Bengaluru) Campus rooftop solar power plant, Tata Power Solar was one of the prominent EPCs.

Some small EPCs choose to focus only on residential and small commercial/industrial rooftop solar projects. These are typically small businesses with a local focus.

The dynamics of the solar EPC sector in India are gradually changing.

In the early stages of India’s solar power sector growth (2010-2015), the EPCs and developers formed almost two distinct segments, as most developers were business houses having access to finance but little expertise in solar power plant implementation. But in the last ten years, and especially after 2020, stand-alone EPC firms are shrinking as larger developers are building their own internal EPC capabilities to improve project viability.

With the above trend, stand-alone EPC firms are diversifying their operations to stay viable. The larger ones are forward integrating and trying to develop and own solar power plants themselves. The smaller EPC firms that do not have the financial capability to be developers are focusing on deepening their skills in value-added solutions such as solar power plants with battery storage and solar+green hydrogen projects. Another fast growth avenue for smaller EPCs is the captive solar segment where they work with corporates to build offsite solar power plants for the corporates’ captive consumption.

Skip to content

Skip to content